-

Follow Your Money

Who gets it, Who spends it, Where does it go?

By Kevin Sylvester and Michael Hlinka

-

A GIANT SPIDERWEB OF CASH

Money. Money. Money.

Everybody wants it. Some people have a lot of it. Most don’t have enough.

This book explores where the money you spend actually goes. You can think of the economy as a giant spiderweb. Even something as simple as buying a can of soda has a complicated series of connections around it.

There are the farmers who grow the corn for the sweeteners (who knew?), the people who mine and manufacture the aluminum for the can, the workers at the factory where they make the soda, the people who transport the filled soda cans, and then—finally—the people who own and work in the store that sells the soda to you. And that’s not even the half of it: each person in this web has some costs and then charges something for his or her work. That adds up, leading to the price you pay for any product.

This web has grown even more complex as the economy (making, buying, and selling stuff, roughly speaking) has gone global. Less than 100 years ago, many people got most of their food from local farms or from small shops that got their products from local farms. Simple, right? The food you eat today, however, might come from China, Venezuela, and California. How does it get here? How much does all of that cost?

-

This book will help you find out, by following the threads.

That might help explain why a rise in gas prices 1,000 km (621 miles) from your home means your bag of potato chips will be more expensive next week. It will also tell you what you’re really paying for when you choose regular jeans over fancy designer jeans, and why printer ink is one of the most profitable products on the planet.

Knowledge is a powerful thing. Knowing why something costs so much might make you appreciate it, and the people who get it to you, more. And knowing where your money goes helps you to be a smarter consumer. So where does your money go?

Turn the page and find out.

Warning! The prices for the examples in this book are only estimates and are rounded off. Prices change all the time, so don't go into your local store and say, "Sylvester and Hlinka tell me this apple should cost only 10¢!"

-

What Is Money?

Before we start breaking down where the money goes, we should answer one key question: What the heck is money, anyway?

Basically, money represents the value we place on something—a digital music player, for example, or the time it takes to make a hamburger or deliver 100 newspapers before the sun comes up.

Paper bills and coins and numbers stand in for what we think or agree that something is worth. So if a shopkeeper decides her product is worth $10, then you have to exchange a $10 bill for that product. The government that issues bills backs up that value so the $10 bill will be worth the same $10 when the shopkeeper goes to spend it somewhere else.

The number “10” in your bank account stands for the same thing, and you can either leave it there as a number (as savings) or take it out (as a bill) and spend it as something “real” (the bill) that can be exchanged for something else that’s “real” (a product or service). Got it? Good!

Let’s go spend some money.

The word “salary” (what someone gets paid in a year for doing their job) comes from the Latin word for salt because people in Rome were paid in salt.

-

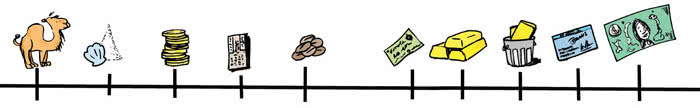

8000 BCE. Barter system. Early humans trade (“barter”) goods for goods (for example, camels for rugs). Sometimes they trade work for goods.

3000 BCE. People start trading a form of money for work or goods. For example, if you have a camel but don’t want to buy a rug, you can still sell the camel to the rug seller if the rug seller gives you “money” that represents the value of the camel. Shells are a common form of money. Salt is used as money in ancient Rome.

1000 BCE. The first coins appear. They are made of gold or silver and have the face of the king, emperor, or other powerful person stamped right into the metal. It’s the powerful person’s way of guaranteeing the value of the coin.

600 CE. Ancient China uses paper money.

1400 CE. The Aztecs use cocoa beans as a kind of money.

1600 CE. Europe begins to make paper money. Yeah, a lot of people lugged around heavy coins for years. Ouch.

1800 CE. Gold is the “standard.” A country can only print as much money as it has gold to back it up. Each British pound, for example, equals one pound of real gold.

1942 CE. Gold standard is ditched. Governments agree that they can print money worth more than the gold they have.

1950 CE. Diners Club becomes the first credit card, allowing diners to eat now and pay later. Lots of cards have followed, and now people can use plastic to pay for almost anything.

TODAY. Money contains all sorts of special security features to stop counterfeiters from copying the bills: holograms, special threads, and even hidden codes and watermarks.

-

Profit: Hurray for Leftovers!

Any discussion of where the money goes leads to a discussion of who gets it. When you buy something, part of the money goes to the people involved in making and selling the product or service. Anything left over after paying all the costs of that product or service is called “profit.”

Imagine a product—a pair of shoes or a great new pair of jeans … or even a cardboard box. There’s the price you pay for it. Then there’s the cost of the materials. So the price you pay minus the cost of materials must be the profit. But, no! There are other costs to pay.

• On top of the cost of materials, there are costs for labor, machinery and manufacturing, the warehouse, and shipping— basically, everything related to production. • And there are the costs of doing business—staff, store rent, electricity for lighting, research into new products, computer systems, and more.

What is left over from the price you paid—and after costs are paid—is profit for someone.

Let’s use a simple example to illustrate this: a $10 cardboard box. The $10 price includes the cost of making the box, which in turn includes the cost of the cardboard, tape, and glue; the wages the company pays its workers; and the cost of storing and shipping the box. But even that’s not the whole story.

-

So, does the box maker get $6 for every box? No way!

The box maker sells the box to a store and the store sells the box to you. The box maker and the store owner both have costs, and they both want to put money back into their own pockets. Let’s add in some more costs and look at who gets what money.

The box maker needs to make a lot of boxes for that 70¢ per box to add up to a living wage! And the same is true for the store owner’s 50¢. The reality is that hardly anyone gets rich selling a few things. The bottom line is often volume: selling a lot of something so that each little bit of profit adds up.

We use the phrase “the bottom line” a lot, but what the heck does it mean? It comes from the world of math. When you add, subtract, or multiply a stack of numbers, the result is at the bottom of the stack. And that bottom number, or “bottom line,” tells you what the other numbers mean after the calculation has been done. When people talk about business costs and profits, they talk about two kinds of profit:

Gross profit is what’s left after the costs of making a product or service and getting it to the market: materials, labor, machinery and manufacturing costs, warehouse costs, shipping—basically, everything related to production.

Net profit is what’s left after all of the other expenses involved in selling the product are deducted. This includes things like rent, lighting, and insurance. Net profit is often referred to as “the bottom line,” and net profit is what the owners of the business get.

In this book, when you see “what’s left” or “profit,” don’t assume that money is all going into one person’s pocket. In most of the cases in this book, “profit” does mean “net profit” but there are always going to be other expenses taken away before any money goes into someone’s pocket.

-

BOX SELLS FOR: $10.00 Less costs per box: Cardboard: $2.00 Tape, glue: 1.00 Shipping, etc.: 1.00 Total costs: $4.00 What’s left: $6.00

BOX-MAKING COSTS (FROM ABOVE): $4.00 Some more costs—calculated per box: Rise in cost of cardboard: $0.10 Rise in labor and machinery costs: 0.10 Cost of some boxes getting ruined in a flood: 0.10 Total costs: $4.30

The box maker sells each box for $5 to the store. That leaves 70¢ for the box maker per box. The store owner will sell the box at a price of $10 but also has costs.

SALE OF BOX TO CUSTOMER: $10.00 Less costs: Cost of box to store: $5.00 Utilities (lighting, etc.): $0.50 Rent: 1.00 Sales staff and losses from other items that don’t sell well: 3.00 What’s left for the store owner per box: $0.50

-

Breakfast

Wake up, sleepyhead, it’s time for breakfast! What better place to start exploring the money web than at the beginning of your day? By the time you get to the kitchen, your eyes are open just wide enough to see a feast. You make a beeline for the orange juice and grab a plate of eggs and toast. Before you head out the door, consider the story behind these eats.

Bacon! The package sells for $3. The farmer gets $1. Farmers play a big role in the food industry, so let’s take a closer look at how they might get and spend that buck. Only about 10¢ is profit, so where does the other 90¢ go?

The leftover $2 that doesn’t get paid to the farmer goes to cover the cost of transportation, storage, refrigeration, packaging, and store costs. Sometimes, a store will add another dollar to the price of the dozen eggs, making the total cost $4. This extra dollar may be what’s left for the store, or it may cover costs such as store advertising.

-

BACON: $3.00 Farmer gets: $1.00 Less: Cost to buy pigs: $0.30 Cost to feed pigs: 0.30 (Pigs eat a lot. This money, of course, goes to other farmers and feed companies.) Cost of running the farm: 0.30 (Tractors, heat, lighting, land tax, and— as you’ll see, this last one pops up everywhere—gas!) Farmer’s profit: $0.10

EGGS (PER DOZEN): $3.00 What the farmer is paid: $1.00 Less: Cost of hen: $0.10 Feed for hen: 0.37 Housing: 0.10 Labor: 0.03 Farmer’s profit: $0.40

BREAD (BY THE LOAF): $2.00 Less: Wheat: $0.20 Turning wheat into flour: 0.10 Other bread ingredients, yeast, etc.: 0.25 Wages, energy: 1.00 Packaging: 0.03 Selling, marketing, storing: 0.20 Transportation: 0.10 Store profit: $0.12

GLASS OF ORANGE JUICE FROM STORE: $0.50 Store profit: $0.10 Transportation: $0.03 Packaging: $0.07 What the orchard gets (for growing and harvesting the oranges): $0.12 Processing (making juice from oranges): $0.18

-

School

A student’s day is filled with economic transactions. Someone bought you those clothes on your back, right? And what about that backpack on your, well, back? Let’s open up the zipper (a big chunk of the cost!) and see what’s inside. It’s full of books, books, books … and so many other things that tell a money-filled story.

And what about that backpack? Let’s say you chose a pretty good one that cost around $30. It should be sturdy enough to last you several years.

Each textbook you use might cost your school $25 to $100 (depending on the subject). However, manufacturing the physical book might cost only about $4 (similar to the cost of the notebook)! Why the big difference—from $4 to $25 or $100? Well, the textbook publisher pays researchers, writers, editors, and artists who “make” the content of the book. The publisher also pays the company that prints and ships the book, or the company that creates the e-book version. Now you know why teachers and parents get so angry when you doodle in the margins or lose your book!

-

PENCIL: $0.15 Less: Wood: $0.01 Graphite: 0.01 Eraser, paint, etc.: 0.01 What’s left: $0.12 Roughly half of that 12¢ goes to the company that makes the pencil. Half goes to the store to pay store costs and have some left over.

BACKPACK: $30.00 Less: Fabric: $6.00 Zippers: 5.00 Labor and manufacturing: 2.00 Other costs: 4.00 Profit to manufacturer: 1.00 Store costs (labor, rent, etc.): 9.00 What’s left: $3.00 The manufacturer spends $17 to make the backpack and sells it to the store for $18. The leftover $1 is the markup for the manufacturer.

NOTEBOOK: $6.00 Less: Cardboard cover: $0.02 Paper inside: 2.50 Spiral binding: 0.01 Other manufacturing costs: 1.47 Profit to manufacturer: 0.20 Store costs (wages, storage, rent): 1.50 Store profit: $0.30 The manufacturer spends money on materials, equipment, and labor, and then builds these into the price it charges the store. Then it adds a bit on top (20¢), which is a “markup” to make some money on each sale.

-

LOOKING GOOD

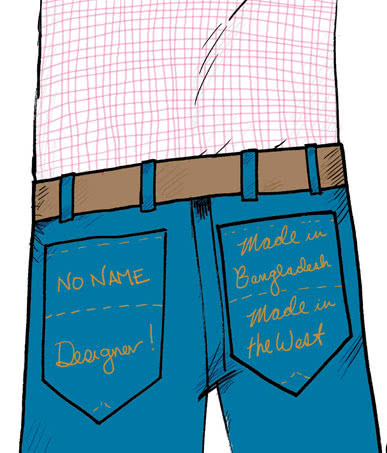

Of course, school isn’t just about pencils and notebooks. You want to look good—or at least be dressed!—before you head out the door. Let’s say you went back-to-school shopping and scored a new pair of jeans.

But wait! Are they regular jeans or designer jeans? The way jeans are made doesn’t differ much between one company and another, but the cost of those jeans depends a lot on the name that’s stitched on the pocket.

REGULAR JEANS: $40.00 Less: Fabric: $3.00 Equipment, shipping: 4.00 Other manufacturing costs: 1.00 Profit to manufacturer: 2.00 Store costs (wages, rent, etc.): 17.00 What’s left: $13.00

DESIGNER JEANS $80.00 Less: Fabric: $3.00 Equipment, shipping: 4.00 Other manufacturing costs: 1.00 Profit to manufacturer: 2.00 Store costs (wages, rent, etc.): 17.00 What’s left: $53.00

-

Your T-shirt contains about 80¢ worth of cotton; the money paid for the cotton in the fabric is split between farmers and harvesters.

Made in Bangladesh

The worker is expected to assemble as many as 10 pairs of jeans per hour. A typical worker makes about $800 a year. Based on a 50-hour workweek, that’s about 30¢ an hour, and 3¢ per pair of jeans.

Made in the West

Wages are higher in the United States and Canada—let’s say $10 an hour. If the worker in Canada makes the same number of pairs of jeans as a worker in Bangladesh, that’s $1 per pair. The 70¢ difference can cut into the manufacturer’s profits, which is one reason many companies have moved their factories a long trip away.

Fuel! The price of fuel is part of this puzzle too. Massive container ships make it possible to move huge quantities of things like jeans around the world. A ship burns a lot of fuel sailing from Bangladesh to North America, but it can also carry millions of pairs of jeans, meaning the cost of fuel is shared among all of those pairs of jeans.

-

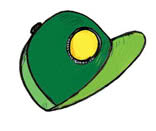

HOLD ON TO YOUR HAT!

That thing on your head says a lot about you. Does your baseball cap reveal your favorite team? Or which movie or band you like the best?

Baseball caps are everywhere. How does the price of one break down? Let’s say you have a really nice custom-fit model, and the price is about $30.

Did you notice that the price on the cap, or on those back-to-school jeans, got higher when the cashier rang up the sale? Why? Taxes.

Taxes go to these and many other services and essentials • Roads • Sewers • Community centers • Libraries • Police • Fire departments • Schools • Hospitals • Services for senior citizens • Help for people who are poor or unemployed

-

Let’s say there’s a 10% sales tax on the $30 hat. That means you pay an additional $3 in tax.

So where does that tax money go? What does the government do with it? Hint: you’re walking on it, driving on it, seeing it overhead, and using it every time you flush.

BASEBALL CAP: $30.00 Less: Fabric, cardboard, thread: $2.00 Labor: 0.40 Equipment, storage, gas: 8.00 Designer’s fee: 2.00 Logo rights: 5.00 Profit to manufacturer: 1.40 Store costs (wages, rent, etc.): 10.00 What’s left: $1.20

-

PIERCED PURCHASES

Getting dressed is a lot more than pulling on basic jeans and a top, right? Extras like belts, necklaces, rings, and earrings come in a wide range of types and prices. Let’s look at earrings as an example of the bling you might wear. You probably buy the cheaper versions, but maybe you pass the expensive shop window once in a while and stare in wonder (or shock)!

How do earrings compare?

You’ve probably seen those ads on TV where some guy yells that he’ll give you “cash for gold” or some similar deal. Sometimes people sell or melt down their jewelry for the cost of the gold or silver. The best time to do this is when the price of these precious metals skyrockets, which often happens when jobs or investments seem uncertain. There’s only so much gold and silver in the world, so they’re always in demand. That means they will always be valuable, even if their cost goes up and down from time to time. Because of this, gold and silver are seen as safe investments.

-

Sellers and buyers rate diamonds by what they call the 4 Cs—carat, cut, color, and clarity. The carat is the weight of the diamond. The bigger a diamond is and the more it sparkles, the more it costs. It costs a diamond mine an average of about $450 to get a diamond it can sell for $500. This means $50 left over.

CHEAP EARRINGS: $8.00 Less: Fake gems: $0.50 Metal: 0.50 Cost to make (wages, equipment): 2.00 Profit to manufacturer: 0.75 Store costs (wages, rent, etc.): 3.25 What’s left: $1.00

DIAMOND EARRINGS: $1,000.00 Less: Diamonds: $500.00 Gold: 100.00 Cost to make (wages, equipment): 200.00 Security costs (safes, security guards, cameras): 50.00 Store costs (wages, rent, etc.): 100.00 What’s left: $50.00

-

SALES

Have you ever paid $20 for something and then gone back to the same store a week later to find it now selling for $15? Does that make you mad? Were you ripped off?

Maybe, but probably not. Sales happen all the time, and for lots of reasons. Usually a store puts items on sale to get rid of its older stock and make room for new products. Here’s how that works.

Sometimes stores sell something too cheap on purpose. This is called a “loss leader.”

The milk at a corner store, for example, might be cheaper than at the big supermarket a block away. The corner store might be purposely “taking a loss” on the milk—something almost everyone buys— to bring shoppers into the store. Those shoppers may just buy other, more marked-up items.

-

Sale! A store buys a shirt for $10 and agrees to pay the supplier later. The store has 90 days to sell the shirt so it can pay back the supplier the $10. The store plans to sell the shirt for $15.

The store offers the shirt to its customers for $15, but no one buys it. Now what? You guessed it: the store puts the shirt on sale. The store cuts the price to $12, hoping to have $2 left over. But let’s say that doesn’t work either.

After another month, the store drops the price to $10. If the shirt sells, the store can at least pay back the supplier. But let’s say there are still no takers.

Now the store makes a decision. It will sell the shirt for $8—yep, even less than it owes for the shirt. Why? Because this strategy brings in $8. The store can use that $8 to purchase something else and then mark up that item to $12. If the store sells that new item at $12, it will have enough money to pay back the $10 it owes for the first shirt.

-

SHOES

Shoes aren’t just great for your feet, they also tell us a lot about the money web. Yes, a lot more goes into shoes than your smelly old socks! Let’s say you paid 65 bucks for a good pair of leather running shoes. And let’s call the company that makes the shoe Viking. Here’s how the chain works:

1

Farmers raise cows for milk or meat. When the cows are slaughtered, the skins can be sold to a tannery for about $1 per skin. The tannery is one link in the chain from raw material to finished shoes.

2

The tannery uses chemicals and machines to turn the skin into leather. It sells the leather to Viking at a cost of about $2 per pair of shoes. The tannery has $1 but it must pay for chemicals and labor from that.

3

The other materials in the shoe—cloth, rubber, metal, foam, plastic— come from other sources. Those materials add up to another $8 or so per pair of shoes, so the total per-pair cost for the materials is now about $10.

4

Viking makes the shoes at its factory. The factory pays its workers about $3 per pair to cut, stitch, and form the materials for shoes.

-

5

Viking’s costs for running the factory (the machines, building, lighting, insurance, etc.) get spread out over thousands of pairs of shoes, but let’s say those costs work out to $2 per pair. The company adds on $1 for shipping. The total per-pair cost of materials, labor, factory, and shipping is about $16.

6

Viking then sells the shoes to a retailer—a shoe store or department store—for about $32 per pair. So Viking has doubled the price, adding another $16 on top of the cost of making and shipping the pair of shoes. But that $16 is not pure profit. Viking has to cover the costs of trying to make better shoes, creating ads to sell them, and ensuring the factory is as safe and modern as possible (and lots more).

7

The retailer then doubles the price again, and adds a touch extra … selling the shoes at $65. So the retailer raises the price $33 per pair, but the retailer also has to pay their costs out of that.

GAS: IT’S THE HIDDEN STORY IN EVERYTHING YOU BUY

How do you get around when you’re heading off to school, doing some shopping, or going to a movie? No matter where you go, you need to get there. And that often means driving. And that means burning fuel. In many ways, fuel is the key to the entire economy.

Follow the money to learn about fuel.

You might hear the term “fossil fuel” a lot when people talk about gas. That’s because the oil that makes the gas we burn for energy actually comes from dinosaur fossils (and lots of other stuff, like ancient plants) that over millions of years have turned into huge amounts of oil.

Of course, all that oil is stored underground, and it costs a lot to get it out, or “extract” it, as they say in the oil business.

Oil companies spend billions of dollars trying to figure out ways to do this. Offshore oil rigs (giant floating platforms with huge drills that dig for oil under the sea) are used in the middle of the ocean and in remote parts of the planet. In other places, the oil is in the ground, but is mixed with lots of dirt, sand, and rock. It’s very expensive to get the oil separated and cleaned.

And that’s only the beginning. The “crude” oil (what comes out of the ground or ocean) also has to be “refined” in huge industrial complexes before it’s clean enough to use in a vehicle.

COST OF RUNNING AN OIL RIG PER DAY: $8,000.00 on land and up to $600,000.00 in the deep sea (includes the cost of the rig itself spread out over the life of a well) Value of oil extracted per day $400,000 to $4,000,000 Gross profit per day $392,000 to $3,400,000!

But that profit range is only if there are no problems. Companies have built million-dollar oil rigs in places like northern Alaska only to find out there’s no oil there. (They often think there’s oil somewhere, but drilling is the only way to know for sure.) That’s a huge loss.

We depend on plentiful and cheap energy to keep prices low and the economy moving. Cheap sources of fuel allow food to travel to your table from the other side of the globe. Huge cargo ships can carry goods—such as MP3 players or shoes—for pennies per item. And the gas that gets pumped into cars also comes from all over the world. But where does the money go? Fill ’er up and let’s find out.

Oil spills can also cost millions or even billions of dollars to clean up; this is a huge cost that oil companies have to be prepared for, although they work very hard to ensure it will never be necessary. When an oil spill happens, there are also long-term and devastating effects on the environment, so safety and caution are extremely important in oil extraction and refinement.

TANK OF GAS AT THE PUMPS: $40.00 Cost for the raw (“crude”) oil: $24.00 Cost for refining crude oil into gasoline: 3.00 Cost for distribution and transportation: 2.40 Profit to oil company (most) and gas station (some): $3.38 Government taxes and fees: 7.20 Storage fee to gas station: 0.02

The price of just about everything is affected by the price of fuel. If there’s a spike in oil prices—say, because of a war or an environmental disaster— the price at the gas pump can rise. Delivery trucks pay more to gas up, and they charge companies more to deliver products. Manufacturers and stores spread that cost out over all of their products. Prices go up a little bit for each product you buy.

Geting Around

Getting around is a big part of everyday life. Which way is best? The decision is complicated: it involves thinking about what’s available and what’s cheapest, fastest, safest, and the most convenient.

Walking is probably the cheapest. It’s free (once you ignore the cost of shoes, socks, clothes, and the food you’ll eat for energy … nothing is ever really free). But there are also cars, bikes, buses, and in some cases cabs. Often a car is the most convenient way of getting around. That’s why there are so many of them in the world. But cars aren’t cheap to run or own.

ONETIME COSTS FOR A SHOPPING TRIP IN A CAR: Let’s say the store is 30 minutes away: Fuel: $3.00 Parking: $5.00 (or maybe $0.00 if you’re at a mall)

TRANSIT TICKET (FOR ONE RIDE ON METRO BUS LINES): $3.00 Less: Driver’s wages: $1.25 Price of buying bus, spread out per trip: 1.25 Fuel: 0.16 Other costs (maintenance): 0.34 What’s left: $0.00

“Other costs” in this case with the bus mean things like insurance, repairs, services, and supplies other than fuel. (For example, you need soap to wash the bus.) In fact, if you just look at the price of a ticket, public transit often loses money. Usually, government pitches in with tax money to cover some costs because public transit is seen as a public benefit, not a benefit only to those who ride it. Governments often contribute to big investments such as new buses, streetcars, rail tracks, and subways.

So what about a $20 cab trip instead? Where does the money go?

The cab driver keeps the $20 usually. But cabbies have huge expenses.

That $20 cab fare pays for gas (maybe as much as $50 a day), maintenance and repairs, the cost of buying the car, the cost of the cab license (which can cost as much as $100,000 a year in a big city), the dispatcher and the dispatch office and phones, and more. All those costs mean that cabbies have to pick up around 20 to 30 rides a day like yours to have any money left over to pay themselves.

Break Time

We don’t know about you, but we’re ready for a break at a coffee shop. All of this information is making us feel a bit dizzy. Time for hot chocolate!

Let’s start with a typical coffee shop chain. We’ll call it Barstucks. You stroll up to the counter and order a medium hot chocolate for $4. Then you add one of those yummy-looking fancy chocolate bars sitting by the cash register. That’s another $2.

You might be surprised at where the money goes, and how much of it isn’t for the chocolate.

CUP OF HOT CHOCOLATE: $4.00qewr Less: Paper cup: $0.08 Cup sleeve: 0.05 Cup lid: 0.07 Milk: 0.10 Chocolate powder: 0.35 Server’s wages: 0.40 What’s left: $2.95

FANCY CHOCOLATE BAR: $2.00 Less: Chocolate (fair trade): $0.20 Sugar, cocoa butter, other ingredients: 0.02 Bar manufacturing and factory labor: 1.00 Packaging: 0.02 Transportation, storage: 0.10 Store expenses (rent, wages, etc.): 0.46 What’s left: $0.20

The cost of everything that goes into your cup of hot chocolate plus labor is basically a quarter of the total the store charges. What does Barstucks do with the rest of the money? They spend it on things like rent, water, electricity, cleaning, and insurance. Some of the cost of each cup is also spent looking for new techniques and products—research and development (“R&D”).

What would you do for a fancy chocolate bar? How about saying “okay” to a whole family working every single day for one year, and only earning a total of $1,000 to $2,000? Chocolate is one of the most controversial products on the market because most cocoa beans are grown in faraway countries at unfairly low wages and under difficult working conditions, yet the markup can be really steep.

There’s been a movement to get chocolate companies to buy cocoa beans that come from farms or plantations where the pay and conditions for workers are fair. This movement is called “fair trade.” Fair trade means the companies that buy the cocoa beans pay higher prices for them, and those costs get passed on to you and me.

Note: some high-priced bars are guaranteed to be fair trade; others are high priced because they have higher costs for ingredients or packaging or higher markups, but are not necessarily fair trade.

Whichever bar you choose, you are making a choice not only about the price you pay, but also about the way of life for people in other countries.

Foods and drinks have changed global history, and coffee and tea may be more responsible for this than any other edibles.

Demand for tea helped launch a whole fleet of ships as England and Holland raced to control the trade routes to India, China, and the West Indies. Both countries made a bundle, and it was worth the risk of sinking, attack by pirates, and death. To guarantee the supply, European countries took over whole islands and populated them with slaves and indentured workers.

Indentured workers are people who work for a specific number of years in exchange for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter—but no cash. After those years, they are free to go.

There’s a lot of history in that cup.

MUSICAL MOOLAH

Hey! Hey, you! Yes ... I’M TALKING TO YOU! Oh, sorry. I guess you didn’t hear me. I didn’t see your headphones.

We all seem to lead “plugged-in” lives these days. Technology surrounds us, and it has totally changed the way music is made, sold, and enjoyed. There are more than 450 parts in that MP3 player in your pocket and they add up to a pretty expensive music library.

MP3 PLAYER: $199.00 Less: Hard drive: $55.00 Display module: 20.00 Video/multimedia chip: 8.00 Controller chip: 4.00 Various other parts: 20.00 Labor costs: 4.00 Transportation: 1.00 Profit to manufacturer: 40.00 Store rent, utilities, etc.: 20.00 Store wages and advertising: 10.00 Other costs: 9.00 Store profit: $8.00

The way we listen to music has changed dramatically over the last few decades. Almost all music is now downloaded as a digital file, and that’s made things cheaper for consumers. A physical compact disc (CD) costs about $20, but you can download the CD for about $12. And if you want only one song, that costs is about $1.

SINGLE SONG (DOWNLOADED): $1.00 Artist receives: $0.10 Record label receives: 0.30 Online retailer receives: 0.60

You might think it costs a lot less to make a digital CD than the physical CD, but that’s not necessarily true. A huge part of the cost is spent up front, making the music itself. For much of the 20th century, very large corporations did most recordings. But now, many musicians or bands either do their own recording or work with a very small independent studio.

To the right is a rundown of the costs a music company pays to record an album before they make the actual CD. The recording studio isn’t cheap, for example, but that huge bill gets spread out over time.

Plus there are some onetime Other advertising: $8,000 miscellaneous costs. They add up to about $2,000 but do not increase if more recordings are sold

So, it can cost about $50,000 to produce a series of songs.

Legal fees: $1,500 Production fees: $4,200 Engineering, recording: $12,500 Computers, cords, and other equipment: $5,000 Piano tunings: $750 Musicians for backup on the recording: $9,300 Mixing time, additional studio costs: $3,200 Mastering (refining the music): $1,100 Artwork for CD cover: $900 Release party: $2,000 Other advertising: $8,000

CD (ONE OUT OF 10,000 COPIES): $20.00 Less: Materials: $1.50 Production: 6.00 Royalty to artists: 2.00 Transportation/storage: 0.50 Profit to record company: $5.00 What’s left (for store costs, wages, and store profit): $5.00 If the CD is a hit, then the record company and the stores both make more profit because they sell more copies.

DIGITAL CD: $12.00 Less: Production: $6.00 Royalty to artists: 1.00 Profit to record company: $1.00 Online sales company profit: $4.00

One result of the digital revolution in music is the growth of illegal downloading. For some reason, some people don’t see sharing files as the same thing as stealing a hard copy.

But the recording industry and the artists don’t agree. If 1,000 people download an album without paying for it, the artist loses a dollar for each of those illegal downloads, or $1,000 that should be paid to the artist.

COMPUTE THE CASH

Now let’s talk about some high-priced, high-tech stuff—computers. Suppose your family is in the market for a new one.

Let’s peg the price of a laptop at $600. There’s a ton of stuff inside a laptop—from batteries to condenser circuits to fans—and much of it is made by different companies. Who gets what?

COMPUTER: $600.00 Less: Parts: $240.00 Labor: 20.00 Manufacturing equipment: 100.00 Research: 100.00 Profit to manufacturer: 40.00 Store costs: 70.00 Store profit: $30.00

Not everyone can afford a computer, but statistics show that about 80% of U.S. and Canadian households have one

SIX MAJOR PARTS OF A COMPUTER: Monitor: $100 Speaker: $35 Mouse: $20 Processor that runs the computer: $25 Keyboard: $20 Modem: $40

INK CARTRIDGE: $35.00 Less: Ink: $10.00, Plastic: 0.02, Store costs: 0.10, Manufacturer’s markup: 20.00 Store profit: $4.88

When you get around to buying your computer, the nice people at the store may throw in a printer. That’s not because printers cost nothing to make. (A printer often costs about $100 to make and is sold for about the same price; this is called selling “at cost.”) It’s because the store will later make more money selling you ink cartridges to keep the printer printing.

That $20 markup is almost pure profit for the printer cartridge company. Only about $10 of the $35 cost is for the ink, and even that isn’t for the physical ink itself. Companies argue that they spend millions on research, which is true, and have to cover the costs out of the markup, so they add that to their total costs for the ink cartridge.

Even so, there’s still so little real ink in a cartridge that it’s more expensive—by weight—than the same amount of gold.

Paper has an interesting story too. Unlike money, it does grow on trees … sort of! But the paper you put in your printer has traveled a long way from leaf to leaflet. A package of 500 sheets costs about $8.

PACKAGE OF PAPER: $8.00 Less: Pulp for paper: $3.00 Manufacturing costs: 1.00 Transportation: 0.10 Storage, etc.: 1.00 Profit to manufacturer: 0.50 Store rent, wages: 2.00 Store ads, etc.: 0.20 Store profit: $0.20

Washroom Break! There’s paper everywhere. How much does it cost to make a jumbo pack of toilet paper, about 16 rolls’ worth? About the same as 500 sheets of computer paper.

Let's Eat!

Food! Lunchtime, to be precise. Maybe you’re heading to the mall to do some shopping or catch a movie. Every mall has a food court, but not all the food is the same.

The choices seem endless … and so are the ways money is connected to what you stuff in your mouth.

Let’s start at the burger place.

FAST-FOOD BURGER: $4.50 Less: Meat: 0.20 Bun: 0.32 Condiments: 0.10 Wages, rent, heating, etc.: 2.50 What’s left: $1.38

The actual cost of the burger’s ingredients is 62¢ (meat + bun + condiments), but someone has to cook it and serve it. On top of these costs, the burger place has other costs, such as the cost of advertising and wasted food (when items go bad or pass their expiration date).

Most of the jobs at fast-food places pay minimum wage. The minimum wage is set by the government, and is the lowest amount an employer can legally pay someone for work. The actual amount depends on where you live, but usually minimum wage is between $7 and $10 an hour.

The cost breakdown for a stir-fry is similar.

STIR-FRY: $4.00 Less: Veggies: 0.50 Rice: 0.10 Frying oil: 0.00001 (basically 0) Plate and cutlery: 0.10 Wages, rent, heating, etc.: 2.50 What’s left: $0.80 The actual cost to make the stir-fry is 70¢, so slightly more than a burger.

SALAD: $3.50 Less: Lettuce: 0.10 Other veggies: 0.20 Dressing: 0.03 Packaging: 0.20 Wages, rent, heating, etc.: 2.50 What’s left: $0.47 The actual cost of the salad fixings is 33¢ (lettuce + dressing + other veggies).

Maybe you’re not into meat and not into a stir-fry. How about a salad? The salad is a bit cheaper than the burger, so let’s examine this cold-veggie option.

MOVIE MADNESS!

Catching a movie is a great way to take a break. You get to be entertained for a couple of hours while stuffing yourself with popcorn, soda, and, well, whatever else you want.

You walk up to the ticket counter and ask for one ticket to Arachnid Boy 5. That’ll be $10. Why so much? Well, movies aren’t cheap …

TOTAL COST FOR A BLOCKBUSTER: $200 MILLION Top three actors: $23 million Everyone else: $3 million Director: $10 million Producers: $15 million Shooting the film: $45 million Special effects (staff, computers, materials, etc.): $65 million Scripting (developing the idea, writing the script): $10 million Rights to the comic book company: $20 million Music (composer and musicians): $5 million Everything else (set design, editing, etc.): $4 million

MOVIE TICKET: $10.00 Less: Production costs: $2.15 Advertising costs: 1.90 Distribution copies: 0.90 Studio profit: 1.00 Theater wages: 1.00 Other theater costs (rent, etc.): 3.00 Movie theater profit: $0.05

And what about that popcorn? It might sell for $5 but materials only cost about 27¢ (corn kernels, oil, package). That’s a huge moneymaker for the movie theater. You could make the same popcorn at home for about 60¢.

Hmmm. Maybe you’d rather stay home and rent an online movie instead!

These days, many people subscribe to digital movie stores. You pay a monthly fee of, say, $8, and you can watch as many movies as you want on your computer or TV.

COST TO STREAM A MOVIE: Internet streaming: $0.05 License: 0.50 Hardware: 0.10 Wages, etc.: 0.05 Total cost: $0.70 So the company can make a profit of $7.30 if you only watch one movie, but if you watch 10 movies, they could make nothing.

The company can actually lose money if you watch a lot of movies.

Possible pecuniary penalties! (Pecuniary means “relating to money,” by the way.)

Your family could also end up losing money if you watch too many online movies. That’s because your family’s Internet service plan has a limit on how much data you can download in a month. If you go over that limit, prepare to pay a lot in penalties!

GAME VALUE

Don’t feel like watching a movie? Maybe you prefer a good electronic game. Flick on the console, plug in the game, and pay attention.

GAME: $50.00 Less: Cost of research, design: $10.00 Wages, advertising: 10.00 Materials (case, computer chips, etc.) 13.50 Profit to manufacturer: 0.50 Store costs (wages, etc.): 12.00 Store profit: $4.00

The games are pricey, but have you thought about what the consoles cost? Consoles cost a lot to make and develop, and yet many developers sell them to stores for less than it costs to make them—in other words, they purposely sell them at a loss. However, they hope to sell you a lot of compatible games for that console and make their money back that way. Let’s say the console developer sells the console, which costs $363 to make, to the game store for $320; that’s a $43 loss for the developer.

PRICE OF CONSOLE: $399.00 Less: Processor: $106.00 Other components (graphic chips, etc.): 100.00 Manufacturing costs (including labor): 40.00 Research and marketing: 65.00 Hard disk: 52.00 Loss to developer (–43.00) Store costs: 50.00 Store profit: $29.00

Online gaming is a little different. You sign on to a server and play a group game with other people (sometimes with perfect strangers around the planet!). You often pay a set fee of, say, $15 to join.

It depends on the company, but almost all of that fee covers costs, so there are just a few pennies of profit from each $15. If only a few people sign on, the company loses money. If millions sign on, the company makes some money.

GO PLAY OUTSIDE!

Maybe you like playing other kinds of games (or your parents order you to). Or maybe you just like exercise and getting outside. What does it cost to play a sport or get running or bicycling? And where does that money go? Let’s take a look.

Suppose you like baseball. A glove can set you back anywhere from $20 to $200, and is made in much the same way as the pair of shoes we looked at a few pages ago.

How about a baseball?

PRICE OF PROFESSIONAL-LEVEL BASEBALL: $15.00 Less: Leather, rubber, and string: $4.00 Labor: 1.00 Factory costs: 1.00 Profit to manufacturer: 6.00 Store costs: 1.00 Store profit: $2.00

There’s a lot of hand-stitching that needs to be done for one pro baseball—and Major League Baseball orders a whopping million-plus balls a month!

Maybe you don’t like team sports, but still love to move. How much does a bike set you back?

SOCCER Equipment: Shin pads: $10.00 Cleats: 40.00 Shorts: 15.00 Total for equipment: $65.00 Fees for a soccer league: $200.00 for beginner; up to $500.00 for elite Total: $265.00 to $565.00

BIKE: $250.00 Less: Bike frame: $25.00 Tires: 20.00 Chain: 40.00 Bike company’s profit: 52.00 Payroll: 18.00 Rent: 25.00 Advertising: 3.00 Delivery: 5.00 Damaged goods: 8.00 Store costs: 31.00 Licenses and taxes: 4.00 Wages: 4.00 What’s left: $15.00

Lots of times, people choose a sport based on what they can afford. Let’s compare two of the most popular sports, one with little or no equipment and one with lots.

HOCKEY Equipment: Skates: $200.00 Shin pads: 80.00 Pants: 100.00 Elbow pads: 50.00 Shoulder pads: 150.00 Helmet and cage: 150.00 Gloves: 100.00 Stick: 100.00 Tape, socks, clothes: 50.00 Total for equipment: $980.00 Fees for a league: $500.00 for beginner; up to $5,000.00 for elite-level teams Total: $1,480.00 to $5,980.00

Most beginner leagues have volunteer coaches, so most of the cost goes for once-a-week ice time. When you are in the elite leagues, there are sometimes paid coaches as well as numerous games and practices per week. That adds up.

SOCCER Equipment: Shin pads: $10.00 Cleats: 40.00 Shorts: 15.00 Total for equipment: $65.00 Fees for a soccer league: $200.00 for beginner; up to $500.00 for elite Total: $265.00 to $565.00

KA-CHINGTONE: CELL PHONES AND SUCH

Your butt is buzzing. Yes, it’s the sound of the cell phone, an everyday (every minute?) part of life. It’s your parents, saying it’s time to head home for dinner.

The cell phone is an amazing child tracker for parents, and it’s a kind of miracle of the global economy. It contains bits from all over the world.

The case, chips, and display all come from different places, which means the money is also divided up among those places, the manufacturer, and the store.

LCD or plasma display: Japan Microphone: China Speaker: China Keyboard: Japan Camera: U.S., some assembly in China Antenna: U.S. Battery: Taiwan Circuit board: China Heavy metals processing and assembly: Taiwan, China Plastic case: China Total cost: $180

CELL PHONE/SMART PHONE PRICE: $200 TO $500 Profit: $10 to $110

Why is there such a range in prices and profits? It depends on what you buy. If you buy just a phone, you’ll pay a higher price and the store and phone maker get more profit. But if you buy the phone and a data plan, you get a break on the price of the phone. The seller makes less money off the sale of the phone. But the seller will get its money back with every call you make or text you send.

That’s because data plans are the real story of the cost of having a phone— and there are lots of different options.

If you go over your limit for minutes, the cell phone company could charge your parents (who probably pay your bills, rig t?) an extra 50¢ to $1 for every couple of minutes. Ditto for t extras. Penalties! Ouch!

SMART PHONE WITH NO PLAN: $500.00 Less: Materials: $250.00 Labor: 50.00 Research: 12.50 Other costs: 37.50 Taxes: 40.00 What’s left: $110.00

If you buy this directly from the phone manufacturer, they get the money. If you get it from a phone company, then it’s split between them and the company that made the phone.

BASIC DATA PLAN: $50.00/MONTH Onetime activation fee of $30.00: $2.50/month Plus ... the options: Unlimited texting and 500 MB downloads: 15.00/month Unlimited calls: 30.00/month Charges for roaming (calls outside your country) $5.00 to $15.00/month Total cost/month: $52.50 basic to $112.10/month!

The costs add up quickly. Ka-ching indeed!

PIZZA

More food! Dinner this time, and it’s pizza night! You have three options: order in, buy frozen, or make your own pizza from scratch.

When pizza is delivered, ingredients and labor usually make up about half the costs. So, if you order a large pizza for $20, the total bill includes about $5 for the ingredients and $5 for the people making the pizza.

What about making your own pizza? Well, it costs roughly the same amount of money to buy pizza ingredients as it does to tip the delivery person—about $5. So the difference is really about time (and a tiny bit about the packaging). Time might mean something different to your parents. If they are tired at night, they might be willing to pay a little extra to have someone else do the work. But you might love taking the extra time to add the toppings you like and knead the dough. And you’ll be eating healthier, homemade food.

So, the bill is $20 and the delivery person is given $25 and told to “keep the change.” That’s quite the tip. A tip is an optional way of saying “thank you.” Many people who work serving food are paid minimum wage, so a tip tops up the worker’s pay to a better level. People tip at restaurants and coffee shops all the time, usually anywhere from 10% to 20% of the total bill. The staff often split the tips at the end of the day.

LARGE PEPPERONI PIZZA DELIVERED: $20.00 Less : Ingredients: 5.00 Labor: 5.00 Franchise fee (for being part of the pizza store chain): 1.00 Packaging, ads, other materials: 1.00 Fuel for delivery, insurance, other costs: 6.00 What’s left: $2.00

Pizza dough: $0.50 Pizza sauce: 0.50 Mozzarella cheese: 0.50 Pepperoni: 0.50 Labor: 1.00 Storage and other costs: 1.00 Packaging: 0.20 What’s left: $5.80

What’s left covers a profit for the manufacturer, plus costs for the store that sells the frozen pizza, and profit for the store.

What about making your own pizza? Well, it costs roughly the same amount of money to buy pizza ingredients as it does to tip the delivery person—about $5. So the difference is really about time (and a tiny bit about the packaging). Time might mean something different to your parents. If they are tired at night, they might be willing to pay a little extra to have someone else do the work. But you might love taking the extra time to add the toppings you like and knead the dough. And you’ll be eating healthier, homemade food.

SUPERMARKET

Maybe your family is in the mood for something besides pizza, or the fridge is suddenly empty. Time for a trip to the supermarket— home to aisles and aisles of glorious food.

The choices are probably healthier than pizza, and they are certainly fascinating.

MILK: $3.00 Less: Paid to farmer: $1.50 Processing: 0.70 Transportation: 0.30 Storing/packaging: 0.20 What’s left: $0.30

GROUND BEEF: $5.00 Less: Paid to farmer: $1.50 Processing: 1.00 Packaging: 0.20 Transportation: 0.50 Store costs (storage, spoilage, etc): 1.70 What’s left: $0.10

SPAGHETTI SAUCE: $3.00 Less: Ingredients: $0.50 Processing: 0.10 Store costs (wages, etc.): 0.40 Packaging: 0.10 Transportation: 0.10 What’s left: $1.80

FRESH TOMATO: $2.00 Less: Paid to farmer: $0.50 Transportation to store: 0.50 What’s left: 1.00 Real Profit: ??????

Why ????? and no real profit? Well, with “what’s left,” the store must cover its costs (wages, lighting, etc.) and try to have something left over for profit. Supermarkets have one huge concern a lot of other stores don’t—they have to include losses for spoiled food. For example, if the tomatoes go bad in the store or on the way there, that’s all lost money. Food can go bad on the shelves if it doesn’t sell quickly, and stores always have to be ready to lose some money in these cases.

It also costs a lot to store fresh foods and keep them fresh and safe to eat.

Lots of stores are moving away from disposable bags toward reusable ones. Fabric bags are better for the environment and save stores the expense of buying plastic or paper bags.

KEEP WARM, KEEP COOL!

Ah, finally: home sweet home. The spaghetti is bubbling away in the kitchen. You see this because you left the lights on. You’ve also left the fridge open, and you’ve turned the heat way up … but left the window open.

Do you have any idea how much energy that wastes? And energy = money. Let’s use a fairly ordinary two-story house in a large city as an example. Plus, let’s look at what it takes to keep your home secure so that you’ll be warm and cozy!

COST OF KEEPING A HOUSE WARM AND COZY PER MONTH: Electricity: about $100 to $200 Heat: $150 Water: about $50 Phone/Internet: $100 Insurance: $100 Property tax: $300

So the basic cost of keeping a house warm and safe is at least $800 a month before you even consider the costs of renting or owning the house. Yikes!

As the world’s population skyrockets, energy costs are rising and supplies for some traditional energy sources (coal, natural gas, oil) are going down. Not surprisingly, many people are working to find ways to get more energy from the sun or ocean.

HAVING A HOME We won’t get into all the different costs of having a home. But let’s look briefly at some terms and what they mean for where the money goes.

HOUSE, BOUGHT: The money spent to buy a house pays for property (both land and building). And then a house owner will start paying regular (monthly or yearly) fees for heating, lighting, water, property tax, etc.

HOUSE, RENTED: someone else owns the property (land and building) and the renters pay a set amount (usually monthly) to use that property as their home.

APARTMENT, RENTED OR BOUGHT: most people think of apartments as for renting only, but the stacked-up homes in a single building, called condominiums, are basically apartments that are bought. The only difference is that each owner buys one unit in the building and all people in the building pay certain shared costs (for the lobby, roof, lawn, pool, driveway, or parking garage, etc.). The shared costs are paid for with condominium fees.

DOWN PAYMENT: when people buy a home, they often pay a portion of the cost as a lump sum (down payment).

MORTGAGE: after paying the lump sum, they might ask a bank to loan them the rest of the money. The house owner then pays back the house loan (mortgage) plus interest—usually in monthly payments. Paying it off can take 25 or even 30 years. No wonder some homeowners celebrate by burning their mortgage contract when they finish paying!

FURRY FRIENDS

At home, you might cozy up to a cat or dog, dream about having one for a pet, or maybe set your sights on an anaconda. Whatever the critter, pets take a lot of work. Pets are also pretty expensive to buy and to take care of. A purebred whippet, for example, can set you back $1,000. A mutt from the animal shelter might cost $200. When someone buys a dog, they are paying for the dog plus all that went into looking after that puppy from birth to sale.

Cats are cheaper, but they still aren’t free unless you get a kitten from a friend.

Even after that purchase (from free to thousands of dollars), there are the costs of caring for that pet for the rest of its life with you. Basic care means pet food, visits to the vet, cat litter, dog leashes, and so on. Let’s take a look at some of the costs you can expect.

PET FOOD: $20.00 A BAG Less: Ingredients: $12.50 Manufacturing costs: 2.50 Profit to manufacturer: 1.50 Store costs: 2.50 What’s left: $1.00

VET FEES FOR A TYPICAL VISIT (immunization shots maybe): $100 A YEAR

PET INSURANCE (only some people buy this): $200 A YEAR

DOG LICENSE (this goes to local governments to pay for animal control officers and other local costs): $15 A YEAR

KITTY LITTER: $10.00 A BAG Cost to manufacture and sell: $9.00 What’s left: $1.00

There might be plenty of unexpected pet costs as well. What happens if Fluffy scratches the arms of your new leather sofa, or Barney the bulldog leaves a “present” on the rug? Or what if they head out the door one day and don’t come back? Suppose Rover has a fight with a raccoon and gets injured?

“LOST PET” POSTER: Cost of photocopying “Have you seen Stinky?” posters: 100 posters at $0.05 each = $5.00

FIXING FURNITURE: Leather polish: $5.00 Large patch job: $200.00 New sofa: $1,000.00 to $2,000.00

BANK ON IT

How could we forget about banks? Well, we didn’t really. After all, they play a central role in all that money flowing around. You deal with a bank when you spend, save, and withdraw money, or when your family uses a credit card.

Let’s say you decide to break your old piggy bank to see how much money you’ve been able to save up. You have … $100! Cool! You take it to the bank to deposit it. Now imagine you let the money sit there for a year.

Here’s what happens next.

Sometimes banks charge a fee of $1.50 or so when you use an automatic teller machine (ATM) that doesn’t belong to your home bank.

It doesn’t cost the bank that much (by a long shot) to cover the costs of having another bank hand out cash.

The ATM fee is either a kind of penalty to get you to consider switching your money to that bank, or a fee for using an independent machine not connected to any traditional bank.

INTEREST:

a fee paid to use someone else’s money. This matters to you if you have a bank account, because the bank will pay you a fee to use your money while it is in the bank.

Interest is usually paid as a percentage. Suppose the bank pays you 1% interest per year. If you put $100 in your bank account for one year, you would earn $1 from the bank for letting it use your money during that time. The bank lends your money to someone else who needs it. It could be a person who is looking to buy a home (this is a mortgage loan) or it could be a business that needs it to expand. In either case, the bank will get paid back on the loan and receive interest as well. Because the bank wants to make more money than it pays back, it will charge a higher interest (something like 5%) when it loans out your money. However, the bank also has some costs to pay.

1

You deposit $100.00 for one year.

2

The bank loans out $100.00 for one year

3 At the end of the year you take out from the bank your $101.00 ($100.00 deposit + $1.00 interest).

In the meantime, the bank has received $105.00 ($100.00 loan + $5.00 interest) from the person or company it loaned money to.

INTEREST BANK RECEIVES ON $100.00 LOAN: $5.00 Less: Interest paid to you: $1.00 Bank wages: 1.00 Rent: 0.45 Insurance: 0.20 Other bank costs: 1.88 Taxes: 0.19 What’s left: $0.28

So, after deducting all the costs, you made more money on your $100.00 than the bank did!

So why do we say “rich as a banker”? Because banks have millions of customers like you, and plenty of those customers have a lot more than $100 in their accounts. Banks make their money on volume. Imagine getting back 28¢ per $100 times millions and millions of deposits.

The banks do face some risks. They could lose your $100 if they invested it in a company that happened to go out of business, but they’d still have to pay you your interest and your $100 if you want it, so they keep the 28¢ left over.

PLASTIC

These days, more and more transactions are made using plastic cards— both debit cards and credit cards, in person and online. Suppose you want to download some music or buy (right now!) that fantastic jacket. You don’t have any cash, so you ask your mom or dad to pay with a credit card. The answer you hear is, “No, not now.” But why not? After all, isn’t using a credit card easy because it’s kind of like not really paying? Think again! The tricky part is the interest, fees, and penalties that are part of paying with a credit card. Let’s see where the money goes.

CREDIT CARD

Let’s say you choose $100 worth of music to download and it is paid for with a credit card. Your family doesn’t have to pay up immediately. Instead, the amount is recorded as owed and will appear on the next credit card statement. The statement will give a list of all money owed and give a deadline for paying it all back.

If the $100 is paid back by the deadline, there is no interest charged on it. Great! (Or so it seems … In fact, many credit card companies charge a fee, but we’ll get to that later.)

If the $100 is not paid off by the deadline, the credit card company starts to charge interest on the money unpaid. Maybe the interest is 15%. That means that if the money isn’t paid by the end of the year, you (your family) will end up owing more—at least $115.

But wait, you could owe more than that.

First, remember about that fee we mentioned earlier!

This can be anywhere from $5 to $120 per year for the convenience of being able to use the plastic card.

Second, there are penalties. If you fail to make a monthly payment, you get charged a penalty of up to 29% of the total owed. Now that’s another $29 to pay.

PAIR OF SHOES (PAID FOR WITH ABC CREDIT CARD): $100.00 Fee store pays for the transaction: $4.00 What the bank that issued the ABC card gets: $3.00 What the ABC credit card company gets: $1.00 That’s why some stores prefer that you pay cash.

To avoid interest and other charges, a lot of people pay off their balance right away. But if everyone always paid their debts right away, the credit card companies would still make money. How? For every transaction made using a credit card, a credit card company gets money from whoever is selling the product or service. That means that the online music seller pays a fee for that $100 of music downloading too. The same is true for shoes costing $100.

DEBIT CARD

Some people use a debit card instead of a credit card. Basically, a debit card is linked to a person’s bank account. It allows for money in a bank account to pay for a purchase at a store (or online). Convenient, eh? Some of these transactions are free: the bank just deducts the money from your account. Sometimes, however, the bank charges a fee per debit card transaction, but this is usually pretty small—about 25¢. You’d have to use your card a lot for that to add up.

Paying with plastic looks fantastically convenient but there can also be: danger!!

Sometimes people will buy more than they can afford. With a credit card, that means buying more than they can pay off by the credit card deadline. So a great new pair of jeans—wow, on sale for $100!—will cost a whole lot more with fees, interest, and penalties piled on top.

And for debit cards, sometimes people spend more than what’s in their bank accounts. If that happens, the bank can charge high fees and interest on top. Imagine you forget how much you have in your bank account and pay for way too many things with a debit card. The final purchase ($1.50 for a cup of coffee) empties out your bank account. The bank fee could be $35 per transaction for this mistake, which means a $1.50 cup of coffee could end up costing $36.50. Now that’s a pricey drink!

HOW DOES IT ALL ADD UP?

A snack.

You’ve earned it. And you’ll probably never look at it the same way again.

As we said at the beginning, knowing where your money goes helps you be a smarter, more aware consumer. You know who gets paid for the ingredients in that burger, chocolate bar, or milk.

You know something about who gets what out of the money you paid for your baseball cap, and how the shoes on your feet are made.

Maybe you’ll think about more than just the cool guitar solo the next time you slap on your headphones and rock out to your favorite song. How much did the guitar player get paid for that great solo?

And you know that the answer to “What’s left?” can be pretty complicated.

Congratulations! You now know just how complex the world of buying, selling, and making really is. So the next time you feel like complaining about the price of a pizza or hot chocolate or a movie ticket or the bus to go to a movie theater, you’ll get the picture.