-

Africans Thought of It

AMAZING INNOVATIONS

By Bathseba Opini& Richard B. Lee

-

Karibu, Soo Dhawow, Kamogelo, Welcome.

Bathseba picks tea on her father’s farm in Kenya.

A tea plantation in Kenya

My name is Bathseba and I grew up near Keroka, a small town in western Kenya. My family belongs to a cultural group called the Abagusii. As a young girl, I spent lots of time with my parents, grandparents, uncles, and aunts, who taught me about the Abagusii customs by sharing traditional tales, riddles, proverbs, and other wise sayings.

When I wasn’t in school, I helped out with chores on the farm. For example, I helped my mom plant, weed, and harvest millet. She taught me traditional ways of scaring away the birds that came to eat our crops.

I also helped out my dad, who grew tea. I would go with my siblings early in the morning to pick tea. Sometimes we also herded cows, sheep, and goats. This was lots of fun because we would also sing songs and play games while we were out in the field herding animals.

-

Johannesburg is the largest city in South Africa.

Now that I live in Canada, there are many things I miss from my life in Africa: the beautiful natural landscapes, the night sky filled with bright stars, the way the moon seemed to smile down at me, and the wonderful hospitality of African people. But most of all I miss my family and friends, and hearing the stories and proverbs that are part of my cultural heritage. My love for Africa is part of me, and I carry it with me wherever I go. I hope this book will help you understand why I love the people and places of Africa so much.

Ancient ruins in Zimbabwe

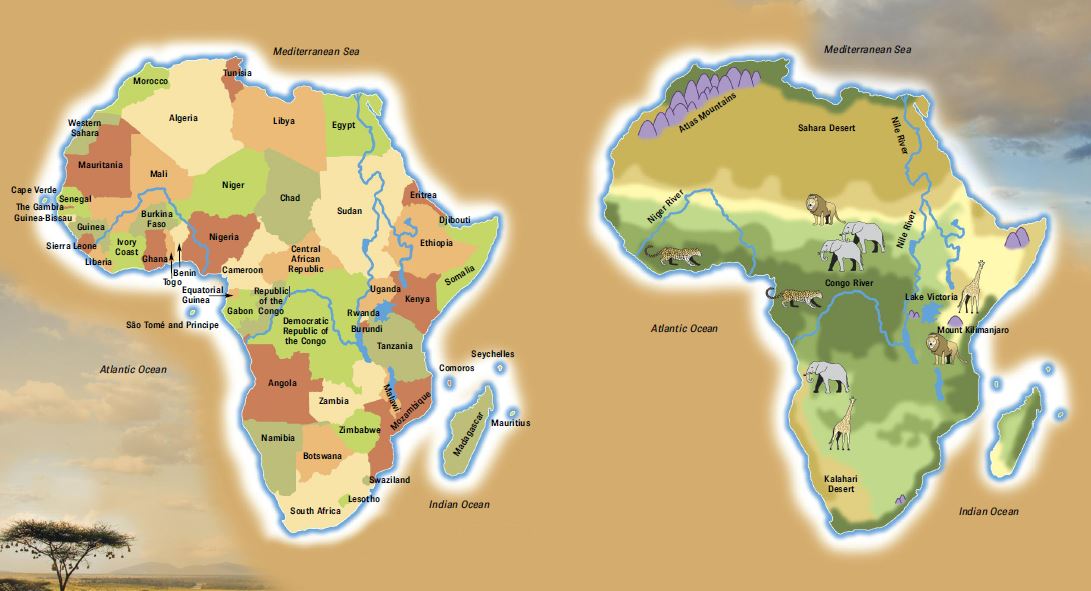

Africa is the world’s second-largest continent and home to almost 1 billion people. Over 800 different ethnic groups live in the 54 countries on the continent. While many Africans live in peaceful rural villages and practice traditional forms of agriculture, Africa has some of the world’s largest and busiest cities, such as Cairo (Egypt), Lagos (Nigeria), Johannesburg (South Africa), and Khartoum (Sudan).

Africa’s history includes the very beginning of human history. The earliest ancestors of modern humans lived in Africa over 4 million years ago. Farming and herding developed thousands of years ago and, over time, great empires arose in west, central, and southern Africa. Countries such as Ghana, Mali, and Zimbabwe take their names from powerful ancient kingdoms.

-

Dried calabash gourds are used for storing liquids, just as we use bottles.

A traditional wooden pillow from Ethiopia

Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania is the highest mountain in Africa.

Today, many aspects of African culture have spread around the globe. For example, plants used in traditional African medicine are now used to make modern medicines and cosmetics. Museums in North America and Europe have large collections of traditional African art. Much of the music that is popular today has been influenced by the sounds and rhythms of African music.

My co-authorrighthard Lee and I invite you to join us on a fascinating journey to discover some of the amazing innovations of African peoples.

-

A Note from Richard Lee

My research in Africa began in 1963, in the village of Dobe in Botswana. At that time, the San people of Dobe still lived a traditional lifestyle, which was very unusual even back then. Women gathered wild nuts, berries, and roots. Men hunted with bows and arrows. I had chosen Dobe because it was a place where the traditional hunting and gathering way of life could still be observed.

One night, I heard a strange melodic sound coming from a neighboring village and went to investigate. The light of a fire revealed a circle of singing women. Men were dancing rhythmically around them. Soon one man staggered and fell into a deep trance. He stood up and moved from person to person, laying his hands on each one—including me. I was witnessing the famous and ancient San medicine dance.

The Gaborone International Convention An ostrich egg used as a water container Centre, Botswana

-

That trip convinced me that Africa was where I wanted to center my life’s work and I have returned many times since then. Life has changed in Dobe, and young people now sit at their computers and surf the internet.

I have been deeply impressed by the African innovations I have seen, many of which are featured in this book. From hunters using leaf beetle larvae to obtain poison for arrows, to people crafting uniquely African tools from metal—the peoples of Africa have demonstrated their outstanding skill at creating useful innovations. This tradition continues today, with many Africans applying their gift for innovation to the challenges of a high-tech world.

I am delighted to be able to share with readers some of the wonders of African innovation.

Richard enjoys a laugh with a friend in Africa.

-

HUNTING

Thousands of years before guns and motor vehicles were invented, African hunters developed skills to help them hunt. There are still some hunters who use the same skills today.

Tracking Techniques

African hunters became very skilled at using animal tracks to help them hunt. For example, young hunters of the San people (sometimes called Bushmen) of Botswana and Namibia learned the following skills from their fathers:

• Hunters learned to recognize the tracks left by many different kinds of animals. They could also tell whether the tracks had been left by a male or female animal, and whether the animal was young or fully grown. From the tracks, hunters could also learn whether the animal was traveling alone or in a herd.

• By carefully examining the tracks, hunters could tell how long ago the animal had been there. If the tracks had been made a few minutes or hours before, there was a good chance the hunters could catch up with the animal. If the tracks had been made a day or two before, the animal was probably too far away.

-

A Maasai man takes a digital photo of fresh lion tracks.

• From the tracks, hunters could tell how quickly the animal was traveling. It might have stopped to eat or rest in the shade, or it might not have stopped at all. This information helped hunters to guess how close or far the animal might be.

• The tracks might also tell hunters if an animal was sick or injured. An animal that is not able to move quickly is easier to hunt.

Over thousands of years, these skills have helped hunters and their families survive in conditions that were often difficult.

The First Scientists?

When the famous astronomer Carl Sagan learned about the tracking techniques used by ancient San hunters, he said they must have been the first scientists. Why would he think so? Like scientists, the hunters looked carefully at evidence (the animal tracks), and tried to understand what it meant.

-

Arrowheads were made in a variety of shapes.

In the modern sport of archery, people practice their skill using a bow and arrow.

Bow and Arrow

Some experts believe that the bow and arrow is an African invention. The earliest evidence is arrow points made from bone, which were discovered in a cave in South Africa. These arrow points are about 60,000 years old.

Early bows were made from wood, and the bowstring was made from animal sinew, animal skin, or plant material. Stone and bone were used to make arrows, but in later times iron was used.

By about 5000 years ago, the bow and arrow had become an important weapon for ancient Egyptians, who used it in battle as well as for hunting.

Ancient Ethiopians were famous for their skill with the bow and arrow. The bows they used were about 2 meters (6 feet) long.

-

Deadly Poisons

A San hunter applies poison from a beetle chrysalis to an arrow.

Putting poison on an arrow made the bow and arrow a more effective weapon for hunting.

Traditional African hunters often used plants to make poison. In some places, hunters used a plant called kombé (pronounced kom-bay). They crushed the plant’s leaves and seeds to make a thick paste that they rubbed on arrows. Arrows poisoned with kombé killed animals almost instantly.

The San people discovered that it was possible to get poison for arrows from the larvae or chrysalids of leaf beetles. (The larvae are young, wingless beetles that look like caterpillars.) This poison did not kill as quickly as kombé, but it was still effective. An arrow with leaf beetle poison could kill an antelope weighing 200 kilograms (440 pounds) in 24 hours. Hunters would follow the animal until it was no longer able to move.